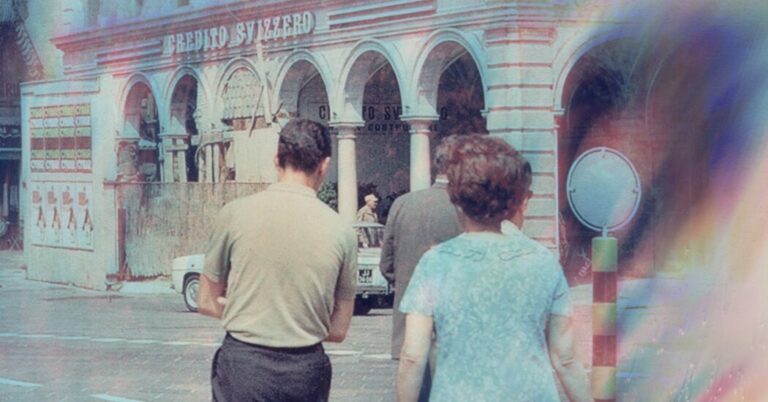

My father only traveled abroad a few times, but when I was growing up, he told me stories of a trip to Europe he took with my parents in 1966, when he was 14. He told me how Nonie loved Switzerland’s clean streets and flower-filled windowsills, the fireplace (with clever recesses on either side for drying clothes or warming bread) in their hillside home outside my father’s hometown of Lugano, and the poverty of their home in Pozzuoli, a town outside Naples, where Nonie’s aunt lined the walls with newspapers for insulation. Sometimes my father would pull out the projector and show us Kodachrome slides.

As an adult, I had been telling him for years to take that trip with me again, at least a shorter version that would take him to Switzerland and Italy, to Lugano and Naples, to show him where his family comes from. But now, as his Alzheimer’s disease progresses, the suggestion took on new meaning. I hoped that looking back at the past might help him live better in the present. A few years ago, I read about reminiscence therapy, a palliative treatment for people with memory problems. In this therapy, participants’ strongest memories are recalled: memories formed between the ages of 10 and 30, during the so-called memory bump period, when personal and generational identities are formed. Reminiscence therapy can take many forms: group therapy, individual sessions with caregivers, co-authoring a book that shares the patient’s story, or conversations between friends. But the goal is the same: to comfort, engage, increase connection, and strengthen the bond between patient and caregiver.

One of the more immersive iterations of reminiscence therapy is a place called Town Square, an adult day care for people with dementia. I visited it shortly after it opened in 2018. The day care consisted of an artificial village that the San Diego Opera designed to look like a 1950s city. It had restaurants, a hair salon, a pet store, a movie theater, a gas station, and a city hall. Town Square hoped to improve the quality of life by recreating the era in which participants’ most vivid memories flared up. The decor provided plenty of talking points. For example, a portrait of Elvis hung in the living room, and a woman who saw it recounted her teenage years and was teleported back in time. “There are no time machines except for humans,” writes Georgi Gospodinov in his novel “Time Shelter,” about a psychiatrist who develops a memory clinic to simulate past eras. I was skeptical of the venture at first. Locking people into a double-locked stage set with oldies playing 24 hours a day sounded grotesque. But what I witnessed there — spontaneous recollection in an upbeat atmosphere — was perhaps the only positive sight of Alzheimer’s I’ve seen.

I wanted to do this for my dad. I wanted to give him joy now that the store that meant the world to him had closed. He didn’t go to daycare, but re-reliving the 1966 trip might have been like reliving the scenes from his youth. In truth, I wanted to replace the terrible memories of the past few years with new ones, not only for him but for myself. Over the past 16 months, I have made countless calls to his doctors, banks, and lawyers, negotiating discounts on interest rates that we could never afford. When he unwittingly undermined my efforts by making random small payments or denying his illness, I got angry, but he never blamed me. In fact, he would swear to try harder. Sometimes he would yell back at me, calling me a nag, a nagging person (a strict, nosy know-it-all, I think). But even when I pushed him and he yelled at me for getting out of the house, I knew he loved me unconditionally and would apologize immediately. He trusted me, even when I didn’t trust myself. For this, the weight of my existence, he demanded nothing in return, nor had any expectations. He never brought up a fight afterwards, and not just because of his illness. He didn’t harbor the resentment I faintly bore for the mistakes he accumulated as his brain shrunk, but I knew these were not his fault. And yet, why didn’t he make a plan? Didn’t he see his own mother suffering and struggling to support her?