How will European governments pay for increased defense spending? They have three options: increase taxes, raise national debt, or issue common EU securities.

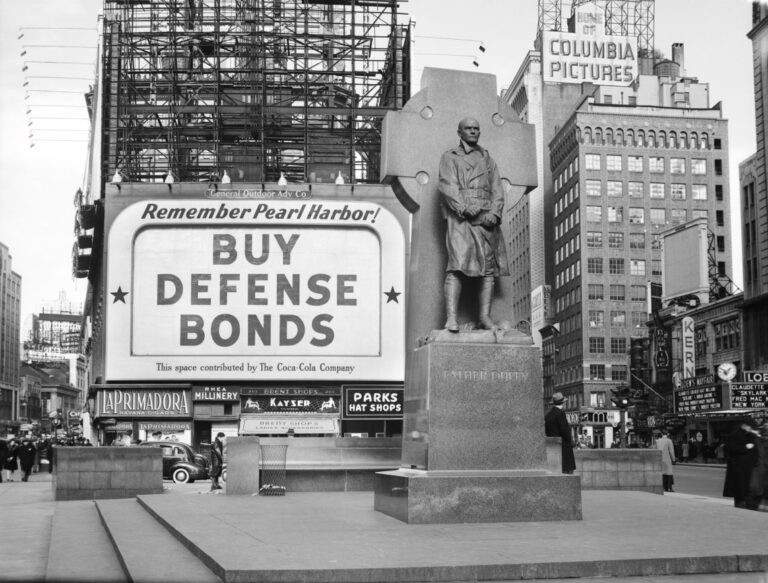

During World War II, more than 80 million Americans bought bonds sold at a discount by the federal government. These bonds, called war bonds, generated more than $180 billion in revenue, financing the US war effort without raising taxes to unpopular levels and keeping inflation in check. Could Europe follow suit? © Getty Images ×

In a nutshell

EU military spending is sure to increase substantially. Governments face unpleasant financing choices. Bonds issued by the European Central Bank are politically attractive.

European nations were unable to develop a credible joint military force. In 1954, France thwarted attempts to establish a European Defense Community (outlined in the 1952 Treaty of Paris), and NATO remained the only common defense umbrella. NATO was based on American resources and equipment, and the nuclear capabilities of the United States, France, and Britain. All was well as long as Western and Central Europe was not threatened.

But that is no longer the case. Russia has repeatedly suggested that it would consider attacking NATO members Estonia and Latvia, as well as Poland and Finland, if the war in Ukraine escalates. While the current US administration is carefully calibrating its response to Russian aggression, complaints about the modest European contribution to the NATO budget continue to come from various quarters in Washington. At the same time, presidential candidate Donald Trump has hinted at the possibility of the US withdrawing from NATO and leaving European countries to fend for themselves.

Inevitable military spending

In Europe, the response to the combined pressures of the looming war and the threat of the withdrawal of US military support has been mixed. Not surprisingly, the eastern member states of the European Union (EU) have taken the Russian threat seriously and responded by significantly increasing their defense spending. In its 2022 report, the European Defense Agency (EDA) noted that defense spending in EU member states hit a “record” of €240 billion, highlighting the “eighth consecutive year of increase.” However, as the graph below shows, spending eight years ago was unwisely low and the overall picture is changing rather slowly.

×

Facts and figures

European Union military spending as a percentage of GDP

At the end of the Cold War in late 1991, average European military spending was 2.4% of gross domestic product (GDP). It is expected to fall to 1.3% in 2015, before rising slightly to 1.6% in 2022 and 2023.

Meanwhile, the Russian Federation is spending 4.1% of its GDP in 2022 and plans to increase this to 7.1% in 2024.

×

Facts and figures

Russian Federation, military expenditure as a percentage of GDP

In other words, by the end of 2024, the EU’s combined defense spending will be around $320 billion, while Russia’s will be an estimated $350-380 billion. The US figure is around $840 billion.

Since the EU economy is much stronger than Russia’s, European countries do not need to make excruciating sacrifices to increase military spending and strengthen deterrence. But one may wonder whether European countries want to just sit back and wait for Russia’s next move. Indeed, maintaining the status quo is not an option. EU defense spending will likely rise and stabilize above 2% of GDP even if tensions ease. Spending will likely increase further if the Ukrainian war drags on and direct NATO intervention becomes likely.

Of the available tools, raising taxes would be the most daunting and painful, at least in the short term, because it would require hitting lower-income earners and the wealthy hardest.

The situation calls for increased military spending. So how can the government raise the money? There are three possible options: increase taxes, increase the national debt, or issue common EU securities.

Europe’s Three Painful Choices

Monetization is a common tool used to finance wars. Essentially, a central bank prints new money and gives it to the government, which then uses it to buy equipment and pay the military. Inevitably, civilian production falls and there is more money in circulation, leading to lower living standards, higher inflation, and possibly an outbreak of social unrest as high inflation leads to changes in income distribution and redistribution.

More about Enrico Colombatto

Raising taxes would be the most cumbersome and painful of the available tools, at least in the short term. It would raise disputes over whether the tax increase should be a national or EU tax, and who would decide how the money should be spent, which could lead to tensions between allies. Moreover, it would not be enough to tax the wealthy, as there are not enough high-income, wealthy taxpayers, and the burden would have to fall more heavily on low-income earners. As a result, countries not in immediate danger of being occupied by an invading army would be less determined to shoulder the financial burden and the temptation to leave Eastern Europe to its fate would be stronger.

Given the above, the most popular idea in European capitals is to increase debt. For example, at the Munich Security Conference in February 2024, Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas proposed setting up a special fund with 100 billion euros of eurobonds issued by the European Central Bank to finance the Ukrainian army and accelerate European rearmament. The idea was supported by French President Emmanuel Macron and European Council President Charles Michel.

Politicians’ preference for Eurobonds

The debt makes political sense for Brussels. With EU member states’ outstanding public debt currently standing at around 14 trillion euros, Michel and Kallas’ proposal would amount to just a 0.7% increase in EU public debt. Financial markets could easily absorb this, especially if officials refrained from calling the bonds “war bonds” and instead pretended to use the proceeds to meet benevolent civilian needs, such as education and infrastructure development in member states. At the same time, member states would transfer equivalent funds to the European defense budget. Under the plan, Brussels could claim that it was advancing the public interest, and national authorities could justify the transfer with a patriotic narrative.

However, the introduction of eurobonds (bonds issued by the ECB as a form of common eurozone debt, not to be confused with regular eurobonds, which are international bonds denominated in foreign currency) has sparked fierce debate among member states, with the idea mainly opposed by Germany and the “frugal” Nordic countries.

Funding urgent military needs with debt also creates a strictly economic problem: who is the lender?

The EU should consider spending at least 1 trillion euros extra on its military over this decade.

When the borrower (national treasury or EU authorities) sells the bond on the financial market, financial investors transfer funds to the borrower, who then spends it on military needs. In other words, investors either increase their savings (for the same amount as the bond they purchased) and reduce their consumption by the same amount, or they keep their total savings constant and reduce resources to finance non-military investments and future growth. In both cases, there is no need to increase the money supply and inflationary pressures are contained.

Size matters too. When expenditures are large and concentrated over a limited period, generating benefits over several years, and repayments spread over 5-10 years, debt financing certainly makes sense. Of course, the risk of borrower default increases. Subscribers have reason to worry, but taxpayers can spread the burden (repayments) even further over time.

In the current circumstances, 100 billion euros will not be enough if the crisis in Eastern Europe continues. The EU should consider at least 1 trillion euros of additional military spending over the decade. The sooner a clear commitment is made, the more credible the EU will be.

In other words, when debt becomes very large, debt repayments make debt financing more and more similar to tax financing, excluding risk premiums.

In fact, choosing a debt strategy often comes close to the possibility that lenders will not be repaid in full, or will be paid in worthless euros, which would reduce taxpayer burdens as the debt disappears the moment the euro weakens (debt is demonetized) or the government defaults.

×

scenario

The EU’s defence efforts could be a huge blow to some countries’ finances, so depending on the ECB’s role, the political packaging could play a key role in defining the two different scenarios.

From Brussels’ perspective, the urgency of rearmament could be an opportunity. It could be an argument for using Eurobonds to finance immediate “emergencies” such as climate change, similar to pandemic-related spending in 2020. Repayment of these bonds could justify a certain form of fiscal centralization, a goal long pursued by the EU bureaucracy.

Scenario 1, almost certain: Brussels issues Eurobonds

The bonds would be purchased by financial investors and paid back in the future through increased taxes (probably levied by Brussels). As with other war bonds, the possibility of partial default (the borrower being unable or unwilling to fulfill the contract) would increase, necessitating the need to provide investors with higher annual interest payments on the bonds (coupons).

Scenario 2, very likely: the ECB buys Eurobonds

Alternatively, a central bank buys eurobonds and prints new money every time a new bond is issued. Eurobonds may also be sold on the market, but are guaranteed by the ECB. When the bonds fall due, the central bank honors its guarantee (by printing new money), in other words, the eurobonds are monetized.

In conclusion, Brussels will likely try to finance rearmament through euro debt guaranteed by Frankfurt and repaid with future euro taxes. National governments will nominally oppose it, but it is unlikely to amount to anything substantial. Ultimately, Europeans may find themselves suffering from increased centralization, higher taxation, and possibly higher inflation as a result of these fiscal decisions.

For industry-specific scenarios and customized geopolitical intelligence, please contact us and we will provide you with more information on our advisory services.

Sign up for our newsletter

Get expert insights delivered to your inbox every week.